Wednesday, January 31, 2007

Miami Vice

Kalen Egan, LOS ANGELES

January 17, 2007 - DVD

I was walking through the aisle at Ralph’s when an impossible deal made me stop in my tracks. It said, essentially, “MIAMI VICE DVD: 19.99. Ralph’s Club Price: 8.00.” I was all, “Whaaaat?” So I asked the clerk if that price was right, and he looked at it and went “Whaaaat?” He rang it up, and the pricing was accurate. He stashed the remaining two copies under the register. I left the store thinking that it was kind of charming the way the Ralph’s clerk dug the cool-looking but ultimately goofy Miami Vice movie enough to save multiple copies for himself. The truth is, I probably wouldn’t have bought the thing if it hadn’t been for the price (in tandem with my kind of insatiable desire to own DVDs), and if I hadn’t, I would perhaps never have realized that this was one of the absolute triumphs of 2006.

Now, I saw Miami Vice in the theater and enjoyed it, but kind of came away feeling like there wasn’t a lot there outside of the visuals and editing. Seeing it at home, however, was... well... the best way I can get at the feeling is by using a sort of trashy, stupid simile, for which I really do want to apologize in advance. Here goes-- to me, watching it this second time felt like jumping into a swimming pool while intoxicated. You’re kind of out of your element, and “this isn’t like normal swimming,” but it feels so good. The water has a new weight against your body, and the fact that something you’ve done a hundred times is now unfamiliar makes it twice as exciting. This was the effect the movie had on me this second time-- it made the familiar, procedural, drug-bust plot seem alien and immediate, and the look of the thing is not just slick and high tech, but exciting in a way that stirs the soul (see: 2001, Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and almost any Herzog movie ever made for similar examples of visuals with the capacity to fill your heart). Yes, it’s true—I see all this in Miami Vice.

And the only explanation I have for this nearly 180-degree turn in appreciation is INLAND EMPIRE. I think it’s valid to let it be known that there are members of this very site who loathed their INLAND experience, and I certainly won’t, and don’t, speak for them now. It’s not a film everyone will love (neither is MV). But for me, watching INLAND was like thinking about movies with a new brain. It asked me to accept and adore what I would under normal circumstances refer to as hideously ugly image quality, and to see the tools used as the only possible way of communicating Lynch’s thick and balmy soup of ideas. It’s not that I just became okay with losing the quality of film—it’s that I was made to prefer this ugly, shit-looking, three-chip digital image to film stock. It told the story better, and INLAND would be worse without it. The filmmaking synchronizes with the visuals, and I realized that with enough revolutionary storytelling, the beauty of the visuals fall into place naturally.

With Miami Vice, I find almost the complete opposite equation. Here, the visuals are so unbelievably enthralling that the story feels perfect and sparkling new. Gunfights take on a new immediacy, even when most of the participants are just ducking behind cars, popping up for potshots. There's an unbelievable camera move during the final shootout, handheld and feeling totally unplanned, in which our perspective urgently races from behind one car to another, while bullets fly overhead. Watch that shot, and see if you don't feel like ducking. Wind whipping through Colin Ferrel's hair as he roars down a street in his convertible-- the moment feels fast and cold. Clandestine meetings in parking garages, when shot on this high-def video, feel like they're really happening-- someone could show up from out of nowhere and catch these guys, because this feels like real, unpredictable life. The difference is in the immediacy; on film, you're aware that there's a hand at the controls. On this video format, you're not so certain. Oh, man, and I don't even want to begin talking about the way the sky flashes in the background, but never quite gives way to rain; it's cinema fucking magic, and gorgeous to behold.

After seeing INLAND, I think I’ve become more open to the idea that image quality and storytelling are somewhat separate, and with enough of one you can feel entirely satisfied with the other. If INLAND is the new brain of digital cinema, asking the viewer to think in a difficult and challenging new way, than Miami Vice is certainly the new eyeballs (okay, okay… at least until this behemoth proves otherwise…), demanding a whole new way of looking at the screen. Visuals this beautiful seem to inspire a different kind of acting, and I think Ferrell and Foxx got kind of a bad rap when the movie came out—check out the way Ferrell and Gong Li nod their heads while looking at each other while sharing a shower. Thanks to Hi-Def digital’s strange, intangible ability to make things immediate, this rang to me like one of the truest cinematic moments of 2006.

There are many, many more individual great moments on display in here. I’d love to write about those extensively, or write about why (in both MV’s and INLAND's case) an extensive knowledge of the directors’ filmographies will vastly improve your experience (not in an elitist, in-jokey way, but in the way that triumphant art rewards those who know the biography and work of its creator). But I think both of those things will have to be saved for another time, or maybe for a personal conversation (and since I think I know most of the few people that might be reading this, that’s not at all out of the question—start me up, man, we’ll talk about this shit all night). For now, just go to your local Ralph’s grocery store and drop the 8 dollars. It’s so worth it if you can catch this wave.

I haven't posted in a while, and I think this article is a bit more breathless and less considered than other ones I've written. Somehow, that feels appropriate. I usually write about older movies, and MV and INLAND are brand new, and I think suggest a lot of wonderful, wonderful possibilities for the future of cinema. It's difficult for me to find a careful, considered way to put that into words... I think it says something that I'm really struggling to explain why the movie based on that funny show and later unofficially adapted into that sweet, bloody video game strikes me as revolutionary. Just see it. And if you've seen it already, see INLAND EMPIRE, then see Miami again.

Posted by

Kalen Egan

at

10:05 PM

5

comments

![]()

Labels: INLAND EMPIRE, Ralph's club, Texas Chain Saw Massacre

Sunday, January 28, 2007

The Hidden Fortress

Jeff GP, NEW YORK CITY

January 19, 2007 - DVD/Landmark Sunshine Cinema

A pair of squabbling bickering best buddies end up stranded in a desert after an enemy pursuit. In a moment of frustration the two separate, only to be captured and reunited. These buddies are Tahei (Minoru Chiaki) and Matakichi (Kamatari Fujiwara), and more than enough have been written about how their Rosencrantz and Guildenstern-ish presence in this picture resembles that of R2-D2 and C-3PO in Star Wars. Some people venture into complete inanity and refer to Star Wars as a remake of The Hidden Fortress. That is not true. This opening scene no doubt meshes with the opening of Star Wars and George Lucas’ movie even takes specific visual and aural cues from The Hidden Fortress, but referring to it as a remake is about as helpful as referring to Boogie Nights as a remake of Raging Bull (meaning not helpful at all). So, to get that out of the way, Star Wars does not sneakily and unjustly remake The Hidden Fortress and not give credit where credit is due. As I initially indicated, having a pair of “fools” to push a story forward is not something Akira Kurosawa nor George Lucas invented, but it is something they used to magnificent effect in producing fun, beautiful, easily digestible fantasy (historical or interstellar) that would influence countless storytellers for ages.

Tahei and Matakichi, tempted by royal riches, end up embroiled in the high-stakes exodus of Princess Yuki (Misa Uehara) from dangerous to safe territory. Her protector is arguably the most charismatic action star in the history of moving pictures, Toshiro Mifune, playing arguably the most skilled fighter in Japan, General Rokurota Makabe. The simplicity of this road actioner is not to be underestimated. It is simple, but this simplicity, matched with good-humored colorful characters and performances, stellar action sequences and beautiful black-and-white landscapes foretell the brilliance that would come from Hollywood’s greatest action pictures and directors (Steven Spielberg and James Cameron to name two).

Along with that Hollywood influence comes the similar trappings that make these Hollywood pictures somewhat disconcerting. In The Hidden Fortress, comic relief Tahai and Matakichi bumble through masses of peasants, many of which are getting shot and killed. Bodies are falling left and right, and it’s played for laughs as the two buddies goofily avoid getting killed.

With all of those corpses aside, and the violence presented as wholly unreal and unaffecting, the flood of humanity is quite striking in contrast with the deserted landscape that occupies most of the movie. For pieces The Hidden Fortress plays and looks the part of a big-budget adventure with expensive expansive sets and tons of extras, but when the gang is not in a town or urban center, they are alone in a tiny-budgeted human comedy. The city limits stop and there is nothing. They wander the countryside unmolested and alone with the landscape. The prospect of a very small outlying community seems impossible. With the exception of a scene where a few mounted troops give them some trouble, the motley band must avoid groups that seem to travel no less than 100 people to a group. The interplay between the personal and epic scope is what would go on to define the great Hollywood yarns of the future. The personal, small nature of movies such as Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lawrence of Arabia and Lord of the Rings is what makes them true successes, not only the action. It is a simple formula, but very difficult to manage well. Akira Kurosawa was one of the early pioneers of such thought, and in turn made movies as fun as they can be. The Hidden Fortress is the least serious I’ve seen Kurosawa be, and the most playful and fun.

A final note:

Big action, big personalities, fantastic music and glorious black and white vistas look detailed and magical when projected on 35mm. Why then, and how dare they, charge full regular admission at the Landmark Sunshine for a screening of The Hidden Fortress on DVD? Nothing is classier than a movie starting with a DVD menu. Fuck you Landmark. If you can’t get a print, why even book it? What’s your problem?

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

3:40 PM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: Akira Kurosawa, Armond White, Boogie Nights, DVD, George Lucas, Landmark Sunshine, Raging Bull, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Star Wars, The Hidden Fortress, Toshiro Mifune

Saturday, January 27, 2007

Brewster McCloud

Harry Potter and the Pantsless Eyelashes

Harry Potter and the Pantsless EyelashesBrewster McCloud is the motion picture debut of the talented and sexy Shelley Duvall. Brewster McCloud is the first motion picture featuring Bud Cort as the titular character; his next would be Harold of Harold and Maude. Brewster McCloud is likely to be (cannot be too sure about this) the only movie where a serial killer leaves bird shit on the bodies. Brewster McCloud is often incredibly funny and irreverent. Brewster McCloud is like M*A*S*H in that an incredibly long action/sporting scene cuts the movie’s sails and brings it to a rather tedious dead halt. Unlike M*A*S*H, this scene is not the climax of the story or the humor, and the movie is forced to struggle to recover (in M*A*S*H, the movie ends). This is a tricky situation that only occurs when a movie is actually genuinely funny, filled to the brim with sillybilly belly laughs. The laughter becomes the norm, and in this case, a long sequence that is unfunny feels far worse than an unfunny scene in a marginally funny movie. The tragedy I speak of is a very long “funny” car chase sequence, shot in characteristic Altman fashion, meaning long shots zooming in and out at a whim, which cause the life-size cars to appear almost like match-box cars. The hyper-kinetic energy of the rest of the movie is reduced to watching a four-year-old play with toys. It is frustrating, because otherwise, Brewster McCloud is classic Altman and a comedy classic. Instead it has been reduced to a mere oddity, but it is so much more, so so much more.

Brewster McCloud bolts out of the gate with a false start and then gets chugging along at a relentless pace. It beings with a woman singing a dreadful rendition of the Star Spangled Banner in the Houston Astrodome. The credits roll over the thing, but the arrogant woman stops singing, berates the band for being out of key and then both the song and the credits start over again (false start). Soon we’re jettisoned to Stacey Keach in old man make-up. He is collecting money from nursing homes. Eventually, Mr. Keach goes careening down a hill in his wheelchair. He hollers quite a bit, very much like (or exactly like) Spike Jonze in the below clip from Jackass: The Movie.

All of this overkill funny leads to what? Does it need to lead to anything? Part of the beauty of Brewster McCloud is the amount of clutter in every frame, clutter or detail, something fans of Wes Anderson may find familiar and comforting. Altman also embraces something that has since become something of a Wes Anderson fixture, which is framing a person or action in the center of widescreen frame, while a cluttered background or oddball action surrounds.

Robert Altman started making movies not as a young man, but as an adult, yet Brewster feels the work of a young, enthused director. The anarchic sunshine that is this picture has a twang of melancholy, but it is first and foremost a whacky comedy. The cherub-faced Mr. Cort is building wings to fly away and become something of a true cherub. Wearing a pair of skimpy briefs, Brewster, with an uncherub-like, sweaty, muscular body does chip-ups. A friend, who works at the local health food store, delivers his order of human bird food, if you can imagine what that is. This girl is just overcome with sexual attraction to this to-be-winged man. Sex is the last thing on Mr. McCloud’s mind, but the gal is willing to take care of things herself. It is one of the funnier scenes in the movie as the girl writhes under covers on Brewster’s bed and he is ardently oblivious. Shelley Duvall is more successful in her seduction, shifting Brewster’s focus just a tiny bit away from flying. His idealist passion to fly away is discovered to be malleable, making Brewster McCloud a coming-of-age story. It is not about sexual awakening, but about dreams and youthful idealism quietly breaking with the influence of the real world and human frailty. Sex is presented as something frail and human, not corrupting. Though Brewster builds himself to be an organic flying machine, like a bird, his avian ideology stumbles a bit with every touch of humanity. Though the movie is not sad and human frailty is celebrated, despite the lost idealism. It would take a man of Altman’s history and stature to communicate this, particularly through comedy, and with its flaws and humanity, Brewster McCloud will be rediscovered and cherished.

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

5:30 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: bird shit, Brewster McCloud, Bud Cort, Harold and Maude, Jackass: The Movie, Michael Murphy, Robert Altman, Shelley Duvall, Spike Jonze, Stacey Keach, Wes Anderson

Sunday, January 21, 2007

Countdown

No images of Countdown anywhere on world wide web.

No images of Countdown anywhere on world wide web.This movie is lost in space.

Worth noting in the Robert Altman canon is the 2nd half of this otherwise typical astronaut movie. The first half is a very calm, cool, collected character drama. Robert Duvall is frustrated (though in a rather subdued manner) that James Caan is picked for a solo mission to the moon. Jealousy runs rampant, though with the restraint you would expect from astronauts and their families. The way the families of astronauts were forced to become politicians, and thus look the cleanest of clean cut is fairly interesting. Moving from The Right Stuff to Apollo 13 to Countdown, every astronaut, their kids, their wives seem more or less physically interchangeable. Serious acting chops carry Caan, Duvall and Altman regular Michael Murphy through the first half with class, despite its rather uneventful nature.

Countdown opens with a Star Trek 2 “fake-out” featuring the aforementioned three leads. They’re prepping for one of the Apollo missions. News comes down the wire that the Soviets are on their way to the moon. The race is on. Countdown was released in 1968, a year before the United States won that leg of the space race and set foot on the rock. The Soviet vs. United States race was very real, but it did not reach the heights of this movie. The race in Countdown is a simple footrace through the stars, though the competition is nowhere in sight.

From the launch of the one-way solo spacecraft to the very last frame of the movie Altman fashions a deliberately paced and tense stretch of drama. As Jimmy Caan goes streaming through space, his communication (and lack of) with the base is just about all we get for 40 minutes. In 1968, all this switch flipping and technospeak must have sounded like nonsense. It still does today, but like all the grounded scenes in United 93 and the engineering babble in Primer the drama takes precedence over understanding what anybody is talking about. The banter between Duvall and Caan is so constant that when it is cut off, due to technical problems, the silence is deafening. All this is well and fine, but totally uninteresting.

Fatalism overtakes the rest of the story as Caan embarks on a suicide mission, and for what? For pride. For manliness. For poetry. Obvious parallels can be drawn between what happens toward the end of this movie and the overreaching themes of the far superior in every way, 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was release mere weeks apart from Countdown. In part, I’m sure 2001 is responsible for the failure of Countdown. The final landing on the moon, in all of its loneliness and silence is shocking. Earth has lost communication and Caan is in the desert. He then embarks on a journey to find a small space station the U.S. landed on the moon not long before. In there he will live awaiting rescue. He has no idea where the station is. Along the way, as time and oxygen starts slipping away he comes across the spacesuited corpses of Soviet astronauts. This scene makes the movie worth watching. It is very, very simple, very quiet, and politically charged. There may be a space-race on Earth, but up there on the moon, there are no countries, no politics, no race. There is only cold loneliness. Mission accomplished.

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

6:05 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: astronauts, Countdown, James Caan, Michael Murphy, primer, Robert Altman, Robert Duvall, Soviet, Star Trek 2 "fake-out", united 93

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Cookie's Fortune

Anne Rapp wrote back-to-back Robert Altman pictures. In 1999 came Cookie’s Fortune. In 2000 came Dr. T and the Women. Both movies are failures. With that said, Dr. T boasts a positively bonkers and somewhat daring ending, which almost makes it worth seeing. Cookie’s Fortune boasts Charles S. Dutton. Needless to say, Ms. Rapp has nary written a picture since.

Anne Rapp wrote Cookie’s Fortune through a looking glass into 1930's Hollywood. An update on the screwball comedy, Robert Altman is the perfect man to pervert such a genre, dead or otherwise. Yet, there is no subversion or perversion in sight, it simply borrows from the least the genre has to offer. Rapp’s script could easily have been tossed aside in the heyday of Cary Grant’s goofy glasses and dead aunts. Frank Capra would have yawned at Ms. Rapp’s hijinks and opted for Clark Gable erecting the Walls of Jericho instead.

In order to “update” the genre, the stage is set in Mississippi, The South, where people are dumber and more gullible, right? Their funny accents allow for screwballiness of epic proportions. Glenn Close buzzes around a house quickly eating a suicide note. Liv Tyler parks up on the sidewalk enough to the point she has a dashboard coated with hundreds of parking tickets. Later on she exclaims she has something like $264 in tickets overdue. Only $264?! This must be 1938, when parking tickets were a nickel! What is this movie?! Where is Robert Altman through all of this?

The actors play the comedy straight, and by straight, I mean stiff. Altman’s comedy must have come by way of his son, Stephen Altman, the production designer. Set around the Easter holiday, the movie is an April shower, or torrential downpour, of pastels. Glenn Close and Julianne Moore are just buried in pink and powder blue light, blossomy fabric. Yes, Julianne Moore is in this picture. It was the same year she gave two of the best performances of the year, with The End of the Affair and Magnolia. In Cookie’s Fortune she plays the half-wit sister to Glenn Close’s maniacal playwriting cupcake face.

The two sisters happen upon the dead body of their aunt, Cookie (when living she is played by the marvelous Patricia Neal). In order to avoid the shame of a suicide in their family, Camille (Glenn Close) decides to cover it up by making it look like a robbery-homicide. This results in Cookie’s best friend, Willis, being tossed in prison. Willis is played by powerhouse Charles S. Dutton. For this role, S. Dutton deflates into a sweet as pie seemingly sexless neighbor, and he manages quite well. I say “sexless,” because while every character seems to have had a spouse or other, Dutton seems blissfully sterile. Now there’s something from 30’s comedy, a sexless, non-threatening, wise, kindly southern black man. Huzzah Ms. Rapp, you captured the 30’s spirit there, right? (wrong!). Still, Dutton shines, a breath of fresh air, as he manages to be the least buffoonish of the bunch. He makes for a strong base as the straight man, and his banter with Ned Beatty is actually quite fun when you cut out every time Beatty is forced to express Willis’ innocence by saying, “I know he’s innocent. We go fishing together.”

Mr. Altman has a way of blending humor and melancholy unlike any other filmmaker. When it works, enough praise cannot be pig-piled any higher. In this case, he is crippled by a script written in a genre that bakes melancholy and despair in an oven of crazy. When screwball comedy worked, it worked from the inside out. Plagued by The Depression and War, Cookie’s Fortune is not. By taking the screwy and attempting to layer in some brand of seriousness this picture mostly falls flat in the mud. Only Charles S. Dutton remains afoot, slowly but surely, rounding the bend, Wild Turkey in hand.

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

1:07 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Anne Rapp, Charles S. Dutton, Cookie's Fortune, Dr. T, Glenn Close, Liv Tyler, Ned Beatty, Robert Altman, Wild Turkey

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Ace in the Hole

Chuck Tatum will eat your puppy.

“I've met a lot of hard-boiled eggs in my time, but you - you're twenty minutes.”

Oh, snap! “Hard-boiled” is correct. Ace in the Hole is a nasty Frankenstein of a picture. Characters are yanked from behind the private eye desk, Venetian blinds and ocean-side mansions of film noir and thrust into the even more nihilistic, more cynical world of politics, money and the most cutthroat of them all, journalism.

Kirk Douglas plays the bullshit-shilling huckster, Chuck Tatum. Tatum has been kicked from major publication to major publication. Always willing to sink his fangs into a great story and run with it, he often takes on a bit of collateral damage with his monster chomps, which gets his shit kicked to the curb. Having torn through all the majors, he is forced to submit to the dregs of the industry, a two-bit rag out of Albuquerque, New Mexico. The folks at this paper wear belts and suspenders both. Tatum stays holed at the paper for a year, expending a greater effort bitching about his long lost New York City than writing exposition for the paper. The stage is set for shit to hit the fan.

On his way to cover a puff piece, Tatum stumbles across a small desert outpost, where a man is trapped in old American Indian cave dwellings. It’s the classic boy-down-the-well tale with a twist of Indian folklore, and a story only as good as the story is long. In order to keep the story a-going and to get the national attention this “hard-boiled egg” of a reporter deserves, Tatum’s willing to keep the poor sucker half-buried and half-alive long enough to kick Albuquerque to the curb and get back to his precious New York City drowning in Pulitzers.

Douglas boils with furor throughout the picture. In the process of bulldozing the townspeople, he’s managed to blackmail the sheriff and the trapped man’s wife into doing his bidding in order to comply with the drama he’s concocted for the paper. In turn, Sheriff wins power and Wife wins cash. Her and her husband own the outpost and she serves up hamburgers and tourist trinkets to the flocking tabloid hounds, all the while planning to ditch the buried man for the big city.

Ace in the Hole belongs to a very specific cross-section of cinema. Titles such as Sweet Smell of Success, A Face in the Crowd, Network and Bamboozled serve a very similar function. Like those titles, Ace in the Hole’s cynicism eventually overwhelms the story (often at its expense), leaving a sickness in the pit of your stomach. It’s easy to get suckered in to the drama (or comedy), until the movie cuts you down the sides with the human comedy (or tragedy), leaving you limp and helpless, but mostly disgusted. Enraging as it is, this picture keeps afloat with snappy dialogue and the no-nonsense Douglas’ infectious, sickening intensity. He carries the charm of a sad-sack private eye, but rather than keep an emotional distance from this dame and that gig, he must act a newspaperman, emotionally involved and manipulating.

I don’t need to tell anyone how much the media influences and shapes history as we understand it. Ace in the Hole takes it a step further, pointing a big fat finger at the media for shaping history, as it happens, not just how it is understood. Billy Wilder’s movie is angry and cynical, a bit exhausting and frustrating, and as an older woman put it on the way out of the theatre, “not entirely heartwarming.”

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

1:26 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Ace in the Hole, Albuquerque, Billy Wilder, bullshit-shilling huckster, journalism, Kirk Douglas, World Trade Center

Monday, January 15, 2007

Absolute Wilson

Spencer Owen, BERKELEY

January 13, 2007 - 35mm/Landmark Shattuck Cinemas

Absolute Wilson is a new documentary about the avant garde theater director Robert Wilson. It's talking heads and archive footage, and it goes: growing up, early work, and then, interspersed with the portrayal of other achievements he's done, several segments summarizing the process behind several of his most landmark works (namely Deafman Glance, KA MOUNTain and GUARDenia Terrace, A Letter for Queen Victoria, Einstein on the Beach, the cancelled CIVIL warS, and The Black Rider). Some of the talking heads are David Byrne (ha ha, for real though), Susan Sontag, Philip Glass, and most importantly a lot of Wilson himself.

I was glad to see this film. I learned a lot about his history and it was delightful to hear him speak about it. It's semi-thrilling to find out about his non-Einstein work, such as his seven-day (!) play staged in Iran (!), KA MOUNTain and GUARDenia Terrace. He's reminiscent of Werner Herzog when he talks about being hospitalized for dehydration; when he comes to in the hospital, he remembers that he's in Iran doing a seven-day play, and so he "tears out the tubes" and goes back to performing. Yet I was reassured that Einstein on the Beach must have definitely been the pinnacle of his work, as it is certainly the pinnacle of Glass's. Tears came to my eyes to hear Robert's sister Suzanne talk about their uber-conservative father's proud reaction to Einstein's landmark performance at the Met, and then see Wilson and Glass take a bow to their rapturous ovation. (Pomegranate Arts, a couple years ago you were advertising a touring version of Einstein, now nothing! What happened?)

On the other hand, after the opening sequence, I was sure I would hate it. Clips of Wilson smiling and saying semi-goofy things (not a problem in themselves) are cut along with some of the more eccentric moments of a handful of his theater productions (also not a problem). Naturally, it's cut to music. This movie has quite a thorough original score, actually, by a gal named Miriam Cutler, and she kicks it off with a real thud by contributing some completely indistinct and chintzy big band jazz -- like, some real weak comedy music. So essentially, we're watching very brief clips of what are supposed to be these immersive, highly surreal, and ... sure, sometimes comical, but nonetheless serious and simply unusual theatrical events ... set to what sounds like royalty-free music. Then they actually go and do a decent job timing the montage to the music. I'm unsure of how accurately I'm conveying the effect, but essentially, we launch by making a thorough mockery of the subject.

Now, I understand the occasional need for serious art to cut through that fog that so many call "pretentiousness" and bring some levity to the table, and I think this was Mrs. Otto-Bernstein's intention. This sequence could have easily worked in their favor if it weren't for the terrible, undermining choice to have it run through with music fit for a Comedy Central special on the upcoming Rob Schneider film. I came in biased towards Mr. Wilson, and after a couple minutes, I was not looking forward to this overview any longer. Imagine the effect it could have on someone who doesn't know a thing about his work. They might be sure he's a pure goofball right away, or a charlatan, or even worse, something like a parodist of Beckett. The most irritating part is that these are all valid criticisms of Wilson, and though I disagree with them, I can easily see them all coming to the surface thanks to this opening treatment.

The movie got better, fortunately, but some of its clip usage seemed arbitrary, and there was a definite overuse of stock footage that had nothing to do with Robert Wilson (a doc pet peeve). As for the rest of Cutler's score, it also seemed stock, but not quite as offensively so, and thankfully it did not all dabble in swing music. My ears perked up at a couple of deliberate Steve Reich rip-offs. I mistook a piece for Reich at one moment, but quickly sussed that it wasn't him; it was a "Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices and Organ" soundalike. It was then quickly followed by a similar shadow-piece, a shadow of "Four Organs" this time. I'm guessing that the original pieces were dropped into the temp track, and they didn't want to pay for them, but for some strange reason really wanted something like them in the movie just that way. Both of these background moments were very brief, and since not minimalist Reich but minimalist Glass had a working relationship with Wilson, they were only tangentially relevant, and only to people who had the same recognition I did. I was relieved to be treated now and then to music from Wilson's works, even some of David Byrne's brass band compositions for The CIVIL warS. These were actually released as an LP called Music for the Knee Plays in 1985, and it's an outstanding record that is to this day in dire need of a CD issue.

Ultimately, Absolute Wilson was a success; I gleaned information and insight about Robert Wilson and his art, and was happy for it. But though it was finally respectful towards its subject, the aesthetic choices along the way -- excepting those that came directly out of the oeuvres of Wilson and his collaborators -- were often truly half-assed and, at times such as its opening sequence, wrong-headed. Maybe this sounds unfair or overcritical, but it really got in the way of being able to take things seriously. Can't a documentary about an aesthetic pioneer at least try to be as dignified as its subject?

(If you're interested in a much more insightful movie specifically about Einstein on the Beach, I recommend tracking down a video of an hour-long TV documentary from 1986 called Einstein on the Beach: The Changing Face of Opera.)

Posted by

Spencer Owen

at

2:25 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: absolute wilson, david byrne, einstein on the beach, katharina otto-bernstein, miriam cutler, philip glass, robert wilson, steve reich, werner herzog

Saturday, January 13, 2007

Idiocracy

Jeff GP, NEW YORK CITY

January 11, 2007 - DVD

If you dumped Idiocracy in a time capsule for 500 years, a man named Beef Supreme may dig it out. Beef Supreme would likely say, “I love this movie!” Mr. Supreme has seen it multiple times, and is confused about the disc-like format and the odd perspective in the photograph of Luke Wilson, or “Not Sure,” on the cover. Will the movies of today survive 500 years? Will the Dantes and Chaucers of today be the Hitchcocks and Malicks of tomorrow? Will the world even exist in 500 years? Mike Judge seems to think so. In a most optimistic dystopian future, Mike Judge fashions an era where the United States still exists! Robots, nor apes, nor supercomputers have taken hold power. Next to the universe of Star Trek, I have rarely seen a future where its government so accurately represents its people and, for the most part, people are happy. They are stupid, but happy. Idiocracy is stupid, but funny. And in this case, that is enough.

It is a rare thing when a comedy can shine despite a cast of unfunny actors (Dax Shepard, Justin Long). The concept, script and mise-en-scene (complete with abysmal computer generated backdrops, 20-mile Costcos and hospitals named “St. God”) all shine through, resulting in some material that is impossible to be unfunny (naming a character Beef Supreme). Luke Wilson and Maya Rudolph play two people who partake in a military hibernation experiment. Needless to say, they are not awoken until one of the great trash avalanches of the 26th century. Wilson and Rudolph do not play the brightest bulbs on the tree, so it takes them a little while to understand what has happened. Dimwits have been breeding at an alarming rate for 500 years, while the intelligentsia are too smart to breed. This, in turn, wipes out global smarts and the world is effectively rendered stupid. This makes Luke Wilson and Maya Rudoolph the smartest people in the world. Comedy ensues.

The scope of this concept is not really grasped until you enter it for yourself. At first glance it seems like a sitcom with an endless tap of funny. That is not the case. It is a very shallow puddle, and sustainable comedy is nearly impossible. Everyone is incredibly stupid and the main characters are extremely boring. There is no character to crack jokes and point out the idiocy of the entire situation or the day-to-day. Luke Wilson is simply concerned with his and Maya Rudolph’s well being. He is too considerate to consider the humor. The only source of perspective comes in the form of an omniscient narrator, who simply fills plot holes and frames the events historically. And yet, funny finds a way. Doctor’s speak lines such as, “So basically it says here you're fucked up, you sound like a fag and your shit's all retarded.” There is a recurring joke referring to the average way Luke Wilson speaks to being “faggy.”

Rita (Maya Rudolph) explains solemnly, “You think Einstein walked around thinking everyone was a bunch of dumbshits?”

President Comacho, the President of the United States, gives a speech to his countrymen decreeing, “Now, I understand everyone’s shit’s emotional right now.”

This is all gut-busting, laughy stuff. It is the Beavis and Butthead world of Mike Judge in live-action form. This is a good thing and I say, if Mike Judge keeps topping himself with dumber and dumber movies, he will soon double-back and make the smartest comedy ever made. Idiocracy is a fairly smart dumb movie, so he’s almost there.

Idiocracy’s theatrical release was a joke (did not open New York City). A joke funnier and dumber than the movie. Its DVD release is a joke. If this title ever ends up on Comedy Central, it will be loved. Cult classic status is just around the corner. It lacks the universality of an Office Space, but it will survive. If I were as optimistic as Mr. Judge, I’d say for 500 years or so, time capsule or no time capsule.

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

11:29 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: faggy, Idiocracy, Luke Wilson, Maya Rudolph, MIke Judge, Office Space, president, Star Trek

Blue Collar

Kalen Egan, LOS ANGELES

January 13, 2007 - DVD

One of the reasons I wanted to do this blog is to help purge myself of the idea that a movie has to accomplish certain things to be considered invaluable. Often we watch something with a kind of unconscious checklist going; Good cinematography? Good acting? How often do you hear or say something like, “no qualms with the story, but what about that dialogue?” I’m so guilty of doing this, it’s not even funny. Usually we can get away with it, because it’s a polite way of discrediting a movie we don’t admire, or the film isn’t really worth thinking very hard about anyway. Other times, though... Other times, we meet a Blue Collar, a film that sticks its livid finger in the barrel of our critical shotgun. We squeeze the "review" trigger, and suddenly we’ve got words like “intent,” “nuance” and “subtext” all blown backwards in our face. When evaluating something like this, relying on our usual concepts of quality and success will only fuck us up, and we risk overlooking something unique and tremendous.

The story begins like this: Zeke (Richard Pryor), Jerry (Harvey Keitel) and Smokey (Yaphet Kotto) are three friends working together on a checker cab assembly line and united, at least in part, by their depression and shared sense of hopelessness. Every day’s another disaster; Zeke is caught in a tax scam, Jerry’s daughter slices up her mouth attempting to create the braces she needs but her father can’t afford, and Smokey drowns his superior intelligence in alcohol, drugs and prostitutes, probably because nobody in his life has ever been willing to consider him as anything but a big, black workhorse. Like anybody in a bad situation, they need something to rail against, and the most apparent causes of their misery are the men running their local labor union. They don’t have any qualm with the union in general, just with the men denying them their basic human rights on a regular basis. So it is that they eventually scheme to rob their own union headquarters. They expect to find bundles of money, but instead come upon a ledger detailing a long series of illegal money loans, all with huge rates of interest. Smokey decides to use it for blackmail.

Up until this point, the movie has been playing by the regular rules—Schrader even includes witty background decorations, like big posters of John Kennedy and Martin Luther King in the union meeting hall, serving almost as a reminder that their efforts toward progress and equality have been subverted into an excuse to simply oppress everybody in the lower class. It’s been a classically “good” movie for an hour, and the viewer probably expects it to stay this way, and perhaps even to offer some insight as to how we as a society can help to rectify these injustices.

Once the blackmail plan is put in action, however, everything changes. The union leaders become almost Machiavellian in their evil deeds, remorselessly terrorizing, creatively murdering, and fork-tonguedly tempting the three guys in a string of melodramatic and unbelievable situations. Suddenly gone is the realism of the early scenes, where we began to know these three men and their families. The film no longer has time to focus its attention on little details; the characters are too busy running for their lives, stabbing each other in the back, and staying up at night gripping baseball bats. The logic behind who gets killed, who gets corrupted, and who becomes an FBI informant is simple-minded at best, and stereotypical at worst. But here’s the thing—each of these “flaws” are essential to the film’s accomplishment. The more fevered and unbelievable it all gets, the more disturbing the movie’s messages become. The further it gets from its internal logic, the closer it comes to fully inhabiting and communicating its central emotion.

This is one of the most pissed off movies I know, a film that sacrifices almost everything for its anger. It depicts characters whose lives are mostly made up of work, debt and drinking. They aren’t well educated, and they aren’t well compensated for the hard work they do. These are people feeling pinned against the wall without a clue how to better their situation, and being slowly driven crazy by a vague awareness of the corruption and oppression that make the bosses around them rich. And just like these three guys, the movie they’re in is prone to hyperbole and irrationality. In the second half, it essentially throws away its effortless sense of realism and honesty, instead becoming totally consumed by outrage and paranoia. It takes the same plunge as Zeke, Jerry and Smokey; as they lose the very values they swore they’d cling to (really, all they had going for them), the film turns its back on plausibility and abandons any sense of responsibility it had toward suggesting a way out of this mess. This isn’t an intelligent study of union corruption; it’s a bath in cold human panic. Whether this is by calculated design or not is irrelevant, and not worth worrying about. The fact that this progression of logic exists—that people think and feel this way, and can eventually be reduced to nothing but blind rage—is all that matters. That’s a tremendously distressing notion, and one Blue Collar follows all the way down to the bottom. It’s not about guys like this; it’s a product of them.

In the end, the movie isn't about answers, it's about questions. One of the film’s posters reads, “Whatever happened to the American dream?” As a tagline, this couldn’t be more perfect. We begin by asking this question of the movie, expecting some kind of reasoned response. Once it's over, we find that we're dizzily asking the question of ourselves, and this time we're asking with a lot more frustration than before. For Christ’s sake, what the hell did happen to the American dream?

Posted by

Kalen Egan

at

6:29 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: American dream, Blue Collar, Harvey Keitel, Machiavellian, Paul Schrader, Richard Pryor, Yaphet Kotto

Friday, January 12, 2007

Vincent and Theo

Jeff GP, NEW YORK CITY

January 10, 2007 - 35mm/IFC Center

Martin Scorsese’s return to form, The Departed, has finally arrived. After two blundering Oscar-chasing failures, Mr. Scorsese delivers what he does best, blood, action and machismo. Let me draw a parallel between The Departed, and how it signaled a career resurgence for a director, who lately, has been dwindling into insignificance. Robert Altman experienced a career resurgence, a return to form and what he does best in 1992, with The Player. An ensemble movie full of famous stars, filled with the angry wit and satire that made him a famous director, like in M*A*S*H, that movie with Alan Alda, or that movie Nashville, where he makes fun of southern people and country music.

With a little bit of embellishment, the above is more or less the boldly moronic attitude I syphon from movie critics and journalists the nation wide. I hear it regurgitated at parties, at the office and from cinematic pundits all over the interweb. Nevermind that he aforementioned Mr. Scorsese’s previous narrative feature, The Aviator, was released to mountains of acclaim from critics, a domestic gross over 100 million dollars and a slew of awards from various places, including a well-deserved Best Actor for Leonardo DiCaprio at the Golden Globes. What a monumental failure. Also, in 2005, Mr. Scorsese made an epic documentary about Bob Dylan called No Direction Home. That was also met with universal acclaim. Good to have you back, Marty.

Now, onto Robert Altman and the task at hand. Before the screening of Thieves Like Us, Christian Science Monitor movie critic and former associate of Mr. Altman, Peter Rainer, made reference to Altman’s revitalization that occurred with The Player. He’s not alone with this popular opinion. Yes, Altman became more commercially viable after The Player, but critics, please.

Vincent and Theo is to be regarded as one of the landmarks of Altman’s varied, prolific and always ambitious movie career. Released theatrically in 1990, Vincent and Theo was conceived and made as a four-hour miniseries for the BBC. I have heard rumors and read that there is a 204-minute cut running around somewhere on a Spanish DVD, and I would love to see it, but for the time being I’ll try sticking to discussion of the 138-minute theatrical cut rather than what could be. Briefly, the removing of whatever footage was shot surely only added to the impressiveness of the performances in a shorter cut, adding a depth, reality and history to every word exchanged. Motivation for certain things may be more explicit in a longer cut, though the conviction with which scenes play out is nothing short of remarkable and believable.

An artist biopic unlike any other, Vincent and Theo succeeds because Vincent van Gogh does not. As his painting is not commercially successful, in no way does it propel the narrative. The narrative is propelled by character, action, choice, sickness, disease and love. Vincent may have painted the pictures, but does this make his brother Theo any less valuable? No. For a large portion of the movie Vincent leaves Paris and spends time with another painter, Paul Gauguin (also still famous). Vincent misses his brother Theo dearly, and it is easy to feel his pain. Theo struggles to conquer syphilis and the mental anguish that accompanies the physical ailment. He courts Jo Bonger, played by an unassuming Dutch actress, Johanna ter Steege. Even though we get to observe both Vincent and Theo throughout their separation, a feeling of longing overwhelms. Their fraternity is split, and it’s hard on them both.

Gabriel Yared’s score is the best of the Altman scores and in one sequence of particular virtuosity a lonely Vincent is overcome by a haunting field of sunflowers. He likes the color yellow, you see? Altman sweeps the camera in and out of the flowers, zooming uncontrollably as Yared’s score churns and churns wildly with bassy orchestration. It is exhilarating.

Tim Roth and Paul Rhys play the titular characters, respectively. Roth certainly looks the part, but as he is not afforded the option of mimicry he instead builds this legendary character from the inside out. There is a quiet to both his soul and his on-screen brother’s. They are the artistic complements to Scorsese’s brutish Jake and Joey LaMotta in Raging Bull. Like Raging Bull, Vincent and Theo plays out with a similarly poetic, simple beauty. Vincent’s painting sequences are not gratuitous. They are sparse, varied and powerful, like Jake LaMotta’s boxing matches. While van Gogh painted a whole hell of a lot more than Jake boxed, they certainly shared a passion for self-destruction and mutilation. So there is an Altman/Scorsese comparison out there that makes sense, and it has nothing to do with fictitious creative slumps.

There is no huge ensemble cast and only a few scenes of overlapping dialogue. The subtler more effective Altman touches are very present here. The characters eat in this movie. Their homes need tidying up. The mise-en-scene does not feel created, but lived in. Vincent looks hungry and thirsty. If there is a scene at a dinner table, the characters act with their mouth full. In one particular scene Johanna ter Steege attempts to one-up Julie Christie’s appetite in McCabe and Mrs. Miller. There is something enormously refreshing about watching characters eat and watching Theo struggle to clean up his flat when Jo first enters. Also refreshing is Altman’s willingness to have his actor’s speak in whatever accent is comfortable. Rather than worrying about someone speaking English with a French accent properly (which makes no sense), the cast and crew worried about what made these human beings tick and how did they live. It is transporting and comforting, and it would be worth it to spend a couple more hours in that world.

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

1:25 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Gabriel Yared, Martin Scorsese, Peter Rainer, Robert Altman, The Aviator, The Player, Tim Roth, van Gogh, Vincent and Theo

Thursday, January 11, 2007

Thieves Like Us

In a typical crime narrative, Keechie falls for a roughneck youth, turned on by his recklessness. In Thieves Like Us, Keechie falls for Bowie, another simpleton, who just happens to make ends by robbing banks. For those who remember Keith Carradine as the smiling cowpoke who meets a chilly demise in McCabe in Mrs. Miller, Thieves Like Us acts as a smiley spin-off (what happened to this smiling goofball between this movie and Nashville that turned him into the man’s man that would go on to play Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok is beyond me). Neither Carradine nor Duvall can keep an elated smile off their face when together. This device matched with Duvall’s commanding physical presence and enormous star-filled eyes make for some serious chemistry. Bowie smiles aw shucks and Keechie returns the smile one hundred bushels over. Shelley Duvall is sexy.

Shelley Duvall is not he the only woman in this picture who delivers a star-making performance and eventually gives a career best performance opposite Jack Nicholson, only to have typecasting effectively ruin the rest of her career. Enter Louise Fletcher, who plays Mattie, the sister-in-law of one of the trio of crooks. Like Nurse Ratched, Mattie is a rock. With a husband in prison and a couple rambunctious youngsters, she has the presence of a high school principal, exuding a maturity that is silencing to adults and children alike. At the same time, unlike Nurse Ratched, she is compassionate and loved and respected. In the final scenes, when Thieves Like Us, when it gives in to its genre conventions and makes a bombastic exit, Fletcher and Duvall share numerous scenes together and it becomes clear what Milos Forman and Stanley Kubrick saw in these fantastic actresses.

Set in 1937 during The American Depression, the soundtrack is jam-packed with radio waves. Believe it or not, Robert Altman was 12 years old in 1937, and he brings his first-person perspective by flooding scenes with the echoes of radio plays and news reports rumbling about "The New Deal,” rather than music. The effect is sometimes silly and distracting, particularly underscoring an intimate scene between Keechie and Bowie. This brand of “comedy” permeates the scenes between the three bank robbers, almost like a far, far less funny Raising Arizona. All the same, Thieves Like Us is not a comedy. It is a serious movie about young love and domesticity. There’s just a bit too much bank robbing in it, even though there isn’t much. It’s like buck shot, and only a few pellets hit the heart. The rest is just buried in your elbow and upper arm. That’s just annoying. Kill me Altman, like I know you can.

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

12:42 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: aw shucks, Keith Carradine, Louise Fletcher, Robert Altman, Shelley Duvall, T-Dub, The New Deal, Thieves Like Us

Tuesday, January 9, 2007

Fellini's Casanova

Hardly easy,

Mostly hard.

Kalen Egan, LOS ANGELES

January 8, 2007 - VHS

Is this a “lost” movie? How can that be? It’s Fellini, it stars Donald Sutherland in his prime, and it appears to have cost a godzillion dollars... but still, it certainly seems lost, doesn’t it? It bears all the hallmarks-- hard to find, a mixed (generally contemptuous) reputation, an epic running time, etc. I mean, you’re a Fellini fan... have you seen it? And what sense does that make when it turns out to be this, one of the largest, craziest and most tragic of all Fellini’s large, crazy and tragic productions? It would be like if Martin Scorsese finally managed to make his long-in-the-works epic about the foundations of violence and turmoil in our urban culture, featuring an important actor giving his most triumphant performance, only to have its reputation sink down near the bottom of his filmography within three years. I mean, c'mon... that wouldn't be no fair kind of world, would it? It’s time to wake this movie up so people can roll around in it at night and place a revolted hand over their bathroom-mirror reflection in the morning. If it is indeed lost, let’s just agree to go turn stuff over until we find the fuckin’ thing, and celebrate it for what it is—an opulent, hilarious, and ultimately disquieting achievement.

Due to the reputation it seems to have inexplicably earned, I started watching Casanova as if it were going to be a long, unpleasant curio. From the opening sequence (in which a barrage of fireworks blast nonstop above Venice while masked merrymakers attempt to lift a gigantic stone statue of Venus, goddess of love and beauty, out of the grand canal… seriously, every scene is like this...) I was floored. There are sights here that deep-fry the brain with their extravagance and imagination, all delivered with Fellini’s patented, disgusted snarl of genius. Maybe that’s the trouble... no matter how beautiful, ironic, and bracing, perhaps two and a half hours of relatively uncollected disdain and self-loathing simply used to be too much to take for most audiences (presently, can we all agree that those days are over?). Indeed, the director seems to have a real distaste for this Casanova character he’s created, who has clearly slipped out of the dankest jail cell in Fellini’s mind (begging the question: should the title be read as “Fellini’s Casanova,” or as “Fellini Is Casanova?” Eh? Maaaybe? ...don’t tolerate this from me, folks...). Imagine the spirit of the final scenes of La Dolce Vita playing variations on itself for a full, epic running time, except smooth Marcello Mastroianni is now instead a penis-face lookin' satyriasist. Shake your legs around if you’re having a good time thinking about this movie.

And let’s talk about the sex, which is far and away the funniest you’ll ever see outside your own bedroom. I’m actually worried that its impact will be lost in my description, but here goes. Casanova and a woman (be she a 7-foot giant, an 80-year-old wannabe mystic, a life-sized porcelain robot, or what have you) will take some of their clothes off (some, mind you, generally excluding key items such as underwear). Then they’ll do an absurd bit of foreplay like hopping around the room together in the wheelbarrow position, before finally lying down missionary style. At this point, Casanova will thrust his entire body forwards and backwards, his face red with crazy strain, while the woman experiences something like rapture. The first time we see this act committed, the lovers are being watched by a detached observer, who states afterward that he’s incredibly impressed by Casanova’s technique... save for the actual sex part, that is, which could probably use a little work. Still – very, very impressive. I don't believe it would be spoiling anything to let you know that Casanova's technique does not improve as the film progresses.

I can’t finish without mentioning the music, which is always up to Fellini’s ambition. Though used sparsely, Nino Rota’s score here is a thing of remarkable invention, dipping more than occasionally into candy-coated schlock to achieve its effect. Whenever one of the aforementioned sex romp sequences kicks into gear, for example, Casanova’s little mechanical rooster—which he apparently takes with him everywhere—springs to life, and Rota provides a fittingly garish and sonically invasive plink-plonk kind of soundtrack to accompany all the zealous shrieking and moaning. Elsewhere, he seems almost to be quoting some of his own La Dolce Vita score, only to agonizingly twist it to achieve Fellini’s subversive aims.

And no question, when the movie has finished, you are left with a powerful sadness. What seemed like an endless string of amusing, pathetic, fantastic sexual exploits is eventually revealed to have been one man’s entire life and legacy. There comes a moment when we are alarmed to discover that Giacamo Casanova’s face has suddenly shriveled (pun unfortunately intended) into that of an old man, and his bloodshot eyes tell a long, excruciating story of regret and desperation. And there we were, laughing along all the way. For me, this discovery was almost unbearably heartbreaking, and altered the entire picture. I’m anxious to explore the film again, but I’m sincerely afraid of how I’ll feel afterward.

There are a small handful of directors who we simply cannot do without. By the same token, we shouldn't have to do without any of their contributions. Were these people to have never existed, than almost any film they made—taken on its own, out of the blue—would come as a sudden, overwhelming, medium-rocking revelation. Fellini is simply not a filmmaker who deserves to be saddled with forgotten films, or lumped in with the likes of actual latter-day mess men like Coppola, Bertolucci, and (put your hand on my back and feel my spine shake) Gilliam. Don’t get me wrong, I certainly wouldn’t want to lose those guys... but I kind of feel like I’d trade any one of them to see this version of Casanova revived.

Posted by

Kalen Egan

at

2:23 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Casanova, Donald Sutherland, Federico Fellini, Heartbreaking, Nino Rota, Penis-face lookin' satyriasist, Venus

Dinner at Eight

January 8, 2007 - DVD

Renowned as a comedy classic, Dinner at Eight is an ensemble picture about a time lost and the depression that accompanies loss, both metaphorical and literal. The American Depression looms heavy over every frame of the picture, which is fairly remarkable, considering the amount glitz and bling it also carries. A former silent movie star, played by John Barrymore, is penniless and drunk. A 3rd generation shipping tycoon, played by John’s brother Lionel Barrymore, is losing his business to the stockholders and his life to illness. An aging stage actress, played by Marie Dressler, is drowning in pelts and forced to sell out a friend to die with her lifestyle intact. These characters are not falling from working class to the bread line, but from extremely rich and famous, to not so rich and a bit infamous. Their young brides and children, groomed for high society in The Roaring 20s are the most worrisome. The older folks make unspoken reference to The Great War, whilst the young ones have no reference or fortitude, because seriousness goes unspoken.

Like A Prairie Home Companion, Dinner at Eight is about a bittersweet last hurrah. Again like Prairie, in preparation for the “hurrah,” the “unspoken” personal and impersonal boils to the surface. Dinner at Eight leisurely introduces its mammoth cast of characters two-by-two. Typically a third enters the scene and then we follow them until it all loops back into itself. The leisurely pace, scene-by-scene is no doubt due to the fact that it is adapted from a stage play, but the structure works wonders for keeping everyone straight, observing them initially in their natural state and then watching the bulldozers come through. Gradually the scenes get quicker and quicker as we get closer to Friday, 8:00PM, and the tension becomes almost unbearable. When the clock tolls seven times it seems as though these characters cannot take another emotional blow, but the quiet cool with which they receive each hit somehow makes it more devastating than crying and screaming. It seems in their nature to cry and scream, as the actors ham up the humor and trifling problems, but for the most part, the outbursts remain trivial and comic. As the serious overwhelms the dinner party, they raise their heads high, full of the knowledge that this Dinner at Eight will be their collective last supper.

A comedy classic? It logically can be regarded as such due to the overwritten theatricality of the script compounded with overacting and the discreetly charming portrayal of the dying bourgeoisie. The comic timing in some scenes is uncanny, and a scene where a distraught servant describes a shockingly bloody incident to the Mrs. of the house is one for the history books. It is clear Dinner at Eight is as well, and it lives on in the films of Robert Altman (most literally in the tagline of the masterpiece Gosford Park – “Tea at Four. Dinner at Eight. Murder at Midnight.”).

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

1:59 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: A Prairie Home Companion, Barrymore, Dinner at Eight, Gosford Park, hurrah, Robert Altman, The Roaring 20s

Monday, January 8, 2007

Vertigo (with a soupçon of INLAND EMPIRE)

January 7, 2007 - 35mm/Cerrito Speakeasy

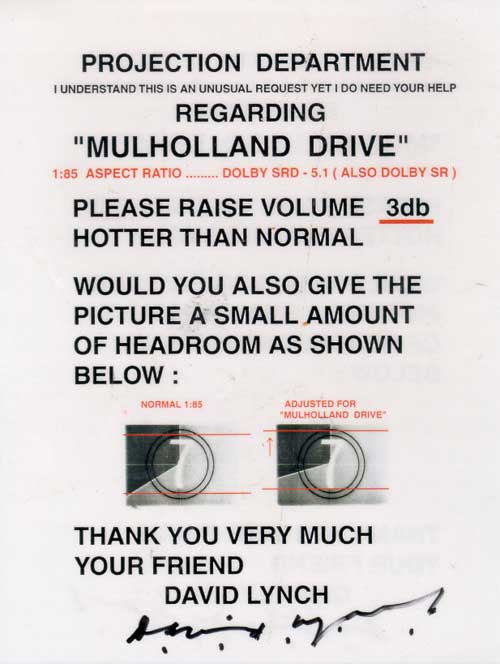

I'm part of the "loved it" half of the microscopic percentage of the world's population that will end up having seen David Lynch's new INLAND EMPIRE. It's a droning behemoth. Yes, Laura Dern wanders slowly through passageways for an endless final 20 minutes of the movie (uh, spoiler), but when I say "droning," I mean the type of sound design that Lynch has been fond of since day one. The first moment of INLAND is a stream of light bursting from a projector in the distance accompanied by a deep, deep bass drone that bursts as well. Leave it to Lynch to associate an illuminating beam emerging from the darkness with the sound of stirring, sudden doom. From there on out, like in all of his other films, the mood is often sonically saturated, especially in the low or low-mid ranges, and the ambience is noted, whether consciously or subconsciously. It was more than cute to discover that Lynch had Mulholland Dr. distributed with a special note instructing the projectionist to (and I paraphrase) turn it the fuck up.

Today I saw Vertigo for the first time at a beautiful theater in El Cerrito, CA called the Cerrito Speakeasy; if you're in the area, do check their schedule, and if something appeals to you, you can grab a healthy dinner and some alcohol while watching the film. I loved the movie, and I was particularly struck by Bernard Hermann's score. His music had always worked for me in other Hitchcock films (and the shower scene is another topic altogether, but you all can just go ahead and stew on that if you must), but never like this. Tonight, the score's effects followed me outside of the theater. It's rare to hear film music so uniquely orchestrated and so conceptually sound that I'm actually glad they went and blanketed the whole movie with it.

The score for Vertigo was put together precisely in a manner that David Lynch has noticed and run with: an unusual, visceral ambience that enhances and deepens the mood that already exists, something that is brought out of the material rather than pasted on top. The difference is that Lynch scored INLAND with rock 'n' roll (pre-existing and of his own creation), musique concrete, and the atonal works of Krzysztof Penderecki; Hitchcock & Hermann, on the other hand, did all their effects with a classical orchestra and without resorting to pure modernism or atonality. Two good ways of doing it, but it is good to be reminded that there are two ways.

I would go deeper into analysis, but I haven't gotten a hold of the soundtrack recording yet, so it would be a lot of remembrance from my recent first exposure, and I'm not sure how well I trust that for getting details right. But I do recall noticing ... isn't it wonderful how, in this first act, with all these scenes of no dialogue, the score actually does the talking, and I'm glad for it? And isn't it interesting how here, in the second half, the music is much more bittersweet and romantic (though far from traditionally so), whereas in the first half it was truly ... eerie, and unnerving? And the opening credits theme ... so gorgeously slippery, the way the arpeggios are really just not in time with each other, with accents marking ... what rhythm exactly? I could go on. How rare!

There are two moments, though, that Hermann can't take credit for (at least I don't think so). In the movie's first scene, Scotty's hanging out with Midge and -- I have to pause right here to call him a fool for not making it work with Midge, because she was way more appealing and grounded than that crazy Madeleine (not to mention Midge being phenomenally cute), but anyway -- there's some peppy string music playing in the background, if a bit low in the mix. I thought, "Well, this is some delightful background music, seems to serve to brighten the mood, a traditional sunny-day everyday tonal element, kicking off the action '50s-style..." Then one of them, I don't recall who, gets up and takes the needle off a record. This turns out to be some kind of foreshadowing for a moment in which (okay, a real spoiler) Scotty's in a hospital, acting like a near-vegetable, and Midge, in her final appearance, puts on a Mozart record, saying that she's been told Mozart should do the trick. When he doesn't respond, she takes it as a sign that she should turn it off. Just as Bernard Hermann brings out the sensations already present, lying in wait to be enhanced, Mozart won't bring Scotty out of his funk, because there's no Mozart -- or Midge -- inside him.

Posted by

Spencer Owen

at

1:53 AM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: Alfred Hitchcock, Bernard Hermann, David Lynch, film music, INLAND EMPIRE, Krzysztof Penderecki, Mulholland Dr., Vertigo

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer

January 6, 2007 - 35mm/Angelika Film Center

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer opens with a welcome bit of cruelty. A young mother working behind a fish stand in an extraordinarily cruddy part of 18th century Paris drops under her table and pops out a little baby, grabs a knife, cuts the cord and pops back up and continues selling a customer. What follows is a brief quick-cut montage of animal butchery and fish gutting, illustrating our newly born protagonists non-discriminatory super-powerful sense of smell. Oh, glorious day! This gooey bowel-filled blitzkrieg is a celebration of filth and a wonderful antidote to the unbeautiful idiocy of this particular scene in Amelie. Could it be, that German director Tom Tykwer has set out to undermine the silliness that plagues the “French” sensibility and humor?

No. Mr. Tykwer chooses not only to embrace this particularly brand of buffoonery, but also to perpetuate the typical and stupid idea of virginal beauty being the most powerful thing in the world. Dopey. Perfume: The Story of a Murderer is based on the German international bestselling book, Das Parfum. What better way for an author to test their craft than to tackle such an abstract wordless wonder as scent? Pages could be devoted to luscious description; an entire novel dedicated to putting a smell in the reader’s nose. Therefore, it would be safe to assume a movie would try to do the same, with image and sound. Yet, this movie attempts to amplify young Jean-Baptiste Grenouille’s abilities with shot after shot of his sniffing nose and, get this, shots of what he smells!

As mentioned, the scent that most captures this young man’s fancy is the smell of a young virgin, and what smells better than a young virgin? Thirteen young virgins mashed into a super-virgin perfume! Thus begins one of the highlights of the movie, a murder montage consisting of Grenouille literally pulling virgins off the street. He hides in the shadows, around corners and out of frame, only to yoink the virgins into the shadows, around corners and out of frame. A great deal of time is spent with one particularly boring red-headed virgin, yielding zero degrees of tension as the young man hunts her down. There in lies the most glaring flaw with Perfume, the lack of character. There is not one complicated, human or interesting character in the movie. Grenouille spends a time as an apprentice to perfumer Giuseppe Baldini, played by Dustin Hoffman. In place of a performance, Mr. Hoffman phones in a completely ludicrous accent. I do not blame him, for how can one utter such lines and look at the stilted doe-eyed expressions of Ben Whishaw and not start speaking in that accent?

None of this does take away from the insanity of the opening scenes of this movie, but it does make the movie an overlong exercise in silliness. Uncalled for silliness haunts French cinema, and Mr. Tykwer, though a German directing a movie in English, made this movie set in France far too cutesy pie for its bleak visuals and murderous subject matter. But hey, let’s crack open a case of virgins and have ourselves a coup.

Posted by

Jeff GP

at

1:16 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Amelie, ben whishaw, cruddy, dustin hoffman, perfume: the story of a murderer, smells, Tom Tykwer, virgins